Mechanism for inhibiting bacterial invasion of colonic epithelia elucidated

A step forward to the development of drugs for ulcerative colitis

A group of researchers led by Specially Appointed Researcher OKUMURA Ryu and Professor TAKEDA Kiyoshi at the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Graduate School of Medicine/Immunology Frontier Research Center, Osaka University elucidated how a gene named Ly6/Plaur domain containing 8 (Lypd8) inhibits bacterial invasion of colonic epithelia, regulating intestinal inflammation.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), such as ulcerative colitis (UC), are intractable diseases with unknown etiology. The number of patients with IBD in Japan has tremendously increased in recent years. However, there are no definitive treatments at present. Recently, the dysfunction of the intestinal mucosal barrier has been thought to be one of the causes for IBD. Indeed, in genetically-modified mice in which the mucosal barrier is defective, intestinal bacteria invade the colonic mucosa, and this causes high susceptibility to intestinal inflammation. Thus, it is important to understand how the mucosal barrier is formed for the elucidation of pathogenesis of IBD and development of effective therapy for IBD. In the colon, where a tremendous number of bacteria exist, colonic epithelial cells are surrounded by the thick mucus and are thereby protected from intestinal bacteria. However, the mechanism by which the mucus layer in the colon inhibits bacterial invasion had been unclear.

To address this issue, this group focused on a gene named Ly6/Plaur domain containing 8 ( Lypd8 ), which is highly and selectively expressed in colonic epithelial cells. This group found that Lypd8 is a highly glycosylated GPI-anchored protein, and is shed into the intestinal lumen. Human LYPD8 is also expressed in the colonic epithelia. This group found that LYPD8 expression decreases in the colon of UC patients. In Lypd8- deficient mice, many intestinal bacteria invaded the inner mucus layer. Flagellated bacteria such as Proteus and Escherichia especially invaded the colonic mucosa in Lypd8- deficient mice. Many flagellated bacteria are known to be pathobionts implicated in intestinal inflammation. Therefore, this group analyzed the sensitivity to dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced intestinal inflammation in Lypd8- deficient mice. Lypd8- deficient mice showed severe DSS-induced colitis compared to wild-type mice. Lypd8 bound to flagella of bacteria. In addition, Lypd8 inhibited the motility of bacteria in semisolid agar plate.

Ly6/PLAUR domain containing 8 (Lypd8), which is a highly glycosylated GPI-anchored protein, is highly and selectively expressed in epithelial cells on the uppermost layer of the intestinal gland and shed into the intestinal lumen. Lypd8 inhibits intestinal bacterial invasion of the colonic mucosa by binding to the intestinal bacteria, and thereby regulates the intestinal inflammation.

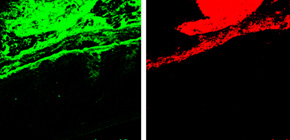

Figure 1. Lypd8 expression in the mouse colon.

Immunostaining with anti-Lypd8 antibody (Lypd8), FISH using bacteria-specific probe (bacteria), and DAPI (colon) of Carnoy’s fixed colon sections. It was found that Lypd8 is highly expressed at the uppermost layer of the intestinal gland and shed into the intestinal lumen.

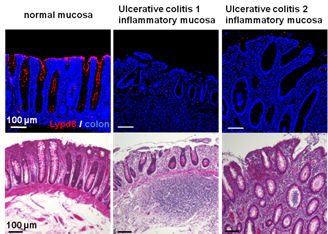

Figure 2. Decrease of Lypd8 expression in the human colon of ulcerative colitis patients.

Immunostaining (upper panel) with anti-Lypd8 antibody (Lypd8) and DAPI (colon) and hematoxylin-eosin staining (lower panel) of human colon sections from the normal mucosa of a colon cancer patient and the inflammatory mucosa of two ulcerative colitis (UC) patients. It was found that Lypd8 expression is severely decreased in the inflamed mucosa of UC patients.

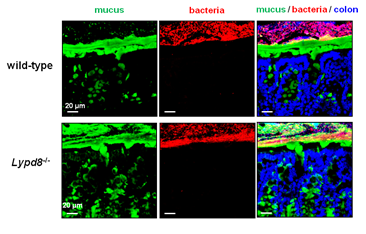

Figure 3. Many intestinal bacteria penetrate into the inner mucus layer in Lypd8 -deficient mice.

Immunostaining with anti-Muc2 antibody (mucus), FISH using bacteria-specific probe (bacteria) and DAPI (colon) of Carnoy’s fixed colon sections. It was observed that many intestinal bacteria penetrate into the inner mucus layer in Lypd8 -deficient mice, but not in wild-type mice.

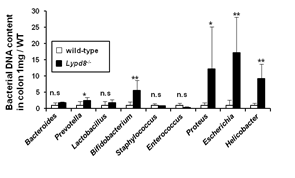

Figure 4. The numbers of flagellated bacteria such as Proteus, Escherichia and Helicobacter are tremendously increased in Lypd8 -/- colonic tissues.

Quantitative PCR of bacterial DNA in colon tissues using bacterial genus–specific primers was performed. Data show each bacterial DNA amount compared to WT mice group. The numbers of Proteus, Escherichia and Helicobacter , all of which are flagellated bacteria, increased in colonic tissues of Lypd8 -deficient mice, compared to those of wild-type mice.

Figure 5. Lypd8 -deficient mice are highly susceptible to dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis.

Survival rate after 2% DSS administration of wild type and Lypd8 -deficient mice is shown. The mortality of Lypd8 -deficient mice was much higher than that of wild-type mice. Lypd8 deficient mice were highly susceptible to DSS-induced colitis.

Figure 6. Lypd8 binds to flagella of P. mirabilis .

A scanning electron microscopic image of P. mirabilis labeled for immunogold detection of the bound Lypd8 is shown. White arrows indicate gold-particles.

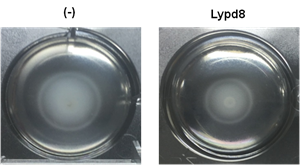

Figure 7. Lypd8 suppresses the motility of P. mirabilis .

Representative photos of P.mirabilis motility in semisolid agar with (right) or without (left) Lypd8 protein at 4 h after incubation are shown. It was found that motility of P. mirabilis was inhibited in semisolid agar containing Lypd8 protein.

To learn more about this research, please view the full research report entitled " Lypd8 promotes the segregation of flagellated microbiota and colonic epithelia " at this page of the Nature website.

Related link

<!--[if gte mso 9]> <w:LsdException Locked="false" Prio