Elucidated the structural basis of the interaction of proteins that induce bacterial cell division

Groundbreaking achievement that will accelerate the development of next-generation antibiotics and micromachines

- Although it has been known that bacterial cell division involves the interaction of the key protein FtsZ and its assisting protein ZapA, the specific mechanism was still unknown. This research clarified this mechanism at the atomic level.

- While cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) captures the static three-dimensional structure of proteins, high-speed atomic force microscopy (HS-AFM) observes their dynamic behavior. By combining these two microscopes, the research group clarified the mechanism by which FtsZ and ZapA interact with.

- By elucidating the mechanism of expansion at the atomic level, precise designs of new antibiotics that can pinpoint and inhibit this function will be developed.

Outlines

A collaborative research group consisting of Professor Hiroyoshi Matsumura and Assistant Professor Ryo Uehara of the College of Life Sciences at Ritsumeikan University, Professor Takayuki Uchihashi of the Graduate School of Science of Nagoya University/The Exploratory Research Center on Life and Living Systems, National Institutes of Natural Sciences, and Specially Appointed Professor (full time) Keiichi Namba, Specially Appointed Assistant Professor (full time) Junso Fujita (at the time) and Specially Appointed Researcher Kazuki Kasai of the Graduate School of Frontier Biosciences at the University of Osaka, has elucidated the ingenious mechanism of bacterial cell division, which proceeds through the dynamic movement of dense protein. This is the world's first demonstration.

In this study, the research group succeeded in capturing the interaction between a protein called FtsZ, which is essential for bacterial cell division, and ZapA, which assists FtsZ function, from both a static "appearance (three-dimensional structure)" and dynamic "movement" perspective. This achievement, which made full use of cutting-edge technologies such as cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and high-speed atomic force microscopy (HS-AFM), is expected to pave the way for the precise design of new antibiotics and the development of micromachines.

Research Background

There are over hundreds of thousands of species of bacteria on the Earth, and they divide to copy themselves to reproduce in extremely harsh environments such as high temperatures, high pressure, and the absence of oxygen. Much remains unknown about the mechanism by which bacteria divide accurately in such harsh environments.

In this study, the researchers focused on a protein called FtsZ, which plays a key role in bacterial cell division. FtsZ is present not only in bacteria but also in algae, some archaea, organelles such as chloroplasts, and some mitochondria, and is an extremely important protein for life, involved in the division of cells and organelles.

Furthermore, FtsZ is important from the perspective of drug discovery. Some bacteria, such as staphylococcus aureus and klebsiella pneumoniae, cause infectious diseases in humans. Bacteria spread infection by multiplying through cell division, so if bacterial division is stopped, the number of bacteria in the body can be reduced and progression of infection will be prevented. Therefore, targeting FtsZ, which plays a key role in cell division, may lead to the treatment of infectious diseases. In fact, the research group has developed antibacterial substance (inhibitors) that target FtsZ (References 1, 2).

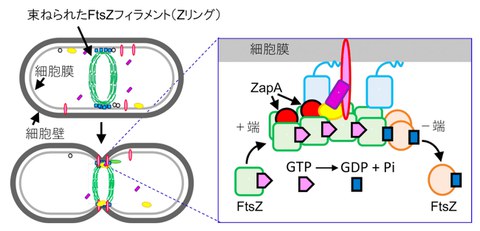

Cell division begins when FtsZ gathers in the center of the cell and forms a ring-shaped structure (Fig. 1, left). In 2023, the research group used cryo-EM to reveal how FtsZ assembles into filaments that resemble strings of beads, and published their findings in Nature Communications (Reference 3), however in this relevant study, the researchers observed only FtsZ, so it was not clear how FtsZ interacts with other proteins.

In this research, when auxiliary proteins such as ZapA, are added to the FtsZ filaments, the ring is bundled tighter, signaling the initiation of cell division (Reference 4). This ring is not simply fixed but seems to be constantly moving due to a phenomenon called treadmilling, in which FtsZ uses an energy molecule called GTP to extend one end and decompose the other (Fig. 1, right).

However, how can proteins continue to move smoothly within these densely packed bundles? In order to solve this mystery, the researchers used the FtsZ and ZapA proteins of klebsiella pneumoniae to elucidate the mechanism of their interaction.

Fig1 The role of FtsZ and ZapA in cell division

FtsZ assembles in the center of the cell like a string (filament), which is bundled together by other proteins such as ZapA. This phenomenon acts as a signal to initiate cell division. FtsZ uses the energy of GTP to cause treadmilling, where one end (positive end) extends while the other end (negative end) is decomposed (right).

Credit: Keiichi Namba

Research Contents

1. Elucidating the "appearance (three-dimensional structure)": Structural analysis using cryo-EM

First, by using a cryo-EM, the researchers succeeded in three-dimensionally observing the complex of ZapA and FtsZ bound together with extremely high precision (approximately 2.7 angstroms), enough to determine the positions of atoms (Fig. 2). As a result, it was found that ZapA binds to multiple FtsZ filaments, forming a ladder-like overall structure.

In this structure, two FtsZ filaments and one FtsZ filament are exquisitely tied by ZapA. It is thought that ZapA acts as a rail on this ladder structure, aligning FtsZ filaments and helping cell division occur. They also found that ZapA and FtsZ interact over a wide area, and that this interaction causes a slight change in the appearance of FtsZ.

Furthermore, through this structure, it is demonstrated that a repulsive force between negative charges occurs in the bundled FtsZ filaments. This repulsive force is thought to be one of the reasons why proteins can move freely even when they are densely bundled together.

Fig. 2 Three-dimensional structure of the ZapA-FtsZ complex demonstrated by cryo-EM

It was revealed that two antiparallel FtsZ filaments and one FtsZ filament are bundled together via the tetrameric ZapA

Credit: Keiichi Namba

2. Elucidating movement: Dynamic analysis using HS-AFM

Next, the research group used HS-AFM to observe in real time how ZapA binds to FtsZ filaments (Fig. 3). This observation revealed that ZapA bundles FtsZ filaments in two different patterns. One is that ZapA binds across two FtsZ filaments, and the other is that it connects adjacent FtsZ filaments on a single FtsZ filament. By utilizing these diverse binding patterns, ZapA is thought to efficiently and flexibly align FtsZ filaments.

Furthermore, this observation clarified that ZapA binding is not static, but is highly dynamic, with binding and dissociation occurring repeatedly over a short period of time. The researchers also found that ZapA tends to remain longer (bind stronger) at locations where two FtsZ filaments are already lined up. They also succeeded in directly capturing the phenomenon of cooperativity, in which successive ZapA molecules are attracted to the site where the ZapA has once bounded and continue to bind. They also captured a phenomenon known as cooperativity occurs when subsequent ZapAs are attracted to the site and bounded successively near the spots where the ZapA was once bounded.

Fig. 3. HS-AFM image of the ZapA-FtsZ complex

ZapA was observed to bind to two FtsZ filaments in two different binding patterns. In the diagram on the right, green indicates FtsZ and red indicates ZapA.

It was confirmed that ZapA bound to two FtsZ filaments, straddling them.

Credit: Keiichi Namba

Social Impact of the Research

The results of this research shed new light at the atomic level on the fundamental question of life: "How do cells divide?" By elucidating this ingenious mechanism, which is at the heart of cell division, the rational design of new antibacterial drugs with fewer side effects that can pinpoint and inhibit only this function will be developed. Furthermore, the biological mechanism by which proteins work together to deform membranes may provide an important blueprint for creating ultra-small machines (micromachines) that can be applied to medical and biotechnology in the future.

This result also demonstrates once again that the approach of combining cryo-EM, which captures static "appearance," with HS-AFM, which captures dynamic "movement," is extremely effective in unraveling the mysteries of life. Of course, more than 30 types of proteins are involved in bacterial cell division, and what has been elucidated this time is only a part of this complex system. This research is an important step forward, and it is expected that research into the full picture of cell division, a biological phenomenon, will be further accelerated.

Notes

The article, “Structural basis for the interaction between the bacterial cell division proteins FtsZ and ZapA,” was published in Nature Communications at DOI: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-60940-w

References

Reference 1: Fujita, J., et al., Structural flexibility of an inhibitor overcomes drug resistance mutations in Staphylococcus aureus FtsZ ACS Chem. Biol., 12(7), 1947-1955 (2017).

Reference 2: Bryan, E., et al., Structural and antibacterial characterization of a new benzamide FtsZ inhibitor with superior bactericidal activity and in vivo efficacy against multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ACS Chem. Biol., 18, 629-642 (2023).

Reference 3: Fujita, J., et al., Structures of a FtsZ single protofilament and a double-helical tube in complex with a monobody Nat. Commun., 14, 4023 (2023).

Reference 4: Squyres, G.R. et al. Single-molecule imaging reveals that Z-ring condensation is essential for cell division in Bacillus subtilis. Nat. Microbiol., 6, 553-562 (2021).