Protein defect leaves sperm chasing their tails

A team led by researchers from Osaka University identify a protein required for electrical signal sensing, which, when defective, causes sperm to swim in circles

With more and more couples seeking assistance to conceive, the steps required for fertilization are being put under the microscope to identify factors that could enhance fertility. In a study published in the journal PNAS, a team led by researchers from Osaka University describe an exciting breakthrough that may aid in future fertility treatments.

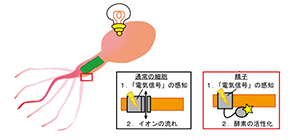

When it comes down to it, sperm have only one job: to fertilize the egg. To do this though, they must first make their way to the fallopian tube, propelled by long tails called flagella. When they near their destination, the sperm become turbo-charged in a process known as capacitation, allowing them to race towards the egg. This enhanced motility is triggered by an influx of calcium ions into the flagellum. While researchers have known for some time that an electrical signal-sensing protein called VSP is expressed in sperm of many animal species, the actual physiological role of this protein was unknown.

Lead author of the study Takafumi Kawai explains, “Determining the physiological role of VSP was the main aim of our study. To do this, we generated a VSP-deficient mouse line so that we could examine VSP-deficient sperm from these animals.”

The first thing the researchers noticed was that the VSP-deficient sperm had a greatly reduced ability to fertilize eggs in vitro . Closer inspection showed that the sperm were swimming around in circles during capacitation, meaning that fewer sperm actually made it to their destination. Defective motility suggested a problem with the flagellum, prompting the researchers to examine these structures in more detail.

“Surprisingly, in normal sperm, a lipid molecule called PIP 2 is concentrated near the top of the flagellum, closer to the head,“ says Dr Kawai. “In the VSP-deficient sperm, PIP 2 was both more abundant and more widely dispersed throughout the flagellum. We also recorded much higher concentrations of calcium ions in the VSP-deficient sperm.”

These findings suggested that VSP plays a major role in ion channel regulation, which ultimately affects motility. The researchers proposed a mechanism whereby VSP is responsible for the polarized distribution of PIP 2 in the flagellum. PIP 2 then activates potassium ion channels, which indirectly causes a localized influx of calcium ions, enhancing motility. In the VSP-deficient sperm, the dispersed PIP 2 causes excessive calcium ion influx which decreases the flexibility of the flagellum, affecting motility.

According to senior author of the study Yasushi Okamura, the discovery of VSP-based regulation of sperm motility has significant implications for male fertility. “We predict that our findings will lead to the development of fertility treatments that enhance sperm motility, increasing the chances of fertilization.”

Fig. Sperm sense an “electrical signal,” resulting in changes in motility. Intracellular enzyme activity is also upregulated in response to the electrical signal.

The article, “Polarized PtdIns(4,5)P 2 distribution mediated by a voltage-sensing phosphatase (VSP) regulates sperm motility,” was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America at DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1916867116 .

Related links