New genome-editing method “cuts back” on unwanted genetic mutations

Researchers at Osaka University develop novel method that can introduce precise modifications to defective genes with fewer safety drawbacks

Gene therapy is an emerging strategy to treat diseases caused by genetic abnormalities. One form of gene therapy involves the direct repair of a defective gene, using genome-editing technology such as CRISPR-Cas9. Despite its therapeutic potential, genome editing can also introduce unwanted and potentially harmful genetic errors that limit its clinical feasibility. In a study published in Genome Research, researchers centered at Osaka University report the use of a modified version of CRISPR-Cas9 that can edit genes with substantially fewer errors.

CRISPR-Cas9 works through the combined action of the Cas9 protein, which cuts DNA, and a short guiding RNA (sgRNA), which tells Cas9 where to make the cut. Together, these two molecules allow virtually any gene in the genome to be targeted for editing. The greater challenge, though, is finding a way to make specific changes to a gene once it has been targeted.

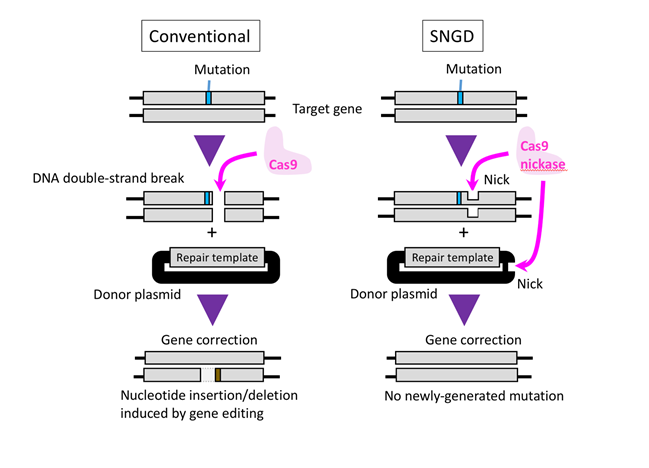

“Cas9 cleaves DNA on both of its strands, essentially splitting the target gene in two,” principal investigator Shinichiro Nakada explains. “The cell tries to repair the damage by ligating the two pieces back together, but the end result is imprecise and often leaves unintended mutations.”

Cells have a precise form of repair that uses donor DNA as a template to correct damage. The template acts as a molecular blueprint, allowing the cell to repair DNA with much greater accuracy. Importantly, by giving cells a different blueprint—in other words, by introducing foreign donor DNA into a cell—highly accurate edits can be made to a defective gene.

“The problem is that Cas9 cleavage is rarely repaired by the precise route,” Nakada adds. “We instead used a modified Cas9 that only ‘nicks’ DNA in one strand, rather than cutting both strands. We discovered that when we nick both the target gene and donor DNA, we can essentially commandeer precise repair to make exact changes to the target gene.”

The researchers found that the nicking technique, which they term Single Nicking in the target Gene and Donor (SNGD), greatly suppresses the rate of unintended genetic mutation compared with the conventional method. In one experiment, the standard technique made potentially-harmful errors over 90% of the time, while SNGD did so less than 5% of the time. Importantly, this precision did not impair the overall performance of the approach, which was able to efficiently achieve the desired genetic edits.

“Our study is a proof of principle that target–donor nicking can achieve accurate genome editing without DNA cleavage, which has significant implications for its use in medicine,” Nakada notes. “There are many diseases for which a precise Cas9 system like this would make gene therapy more cost-effective and safer. We are very excited to see how this technique will be incorporated into the current paradigm of gene editing technologies.”

Figure 1. Cas9 introduces a DNA double-strand break in the target gene, allowing the gene to be edited when a repair template is present. A drawback to the CRISPR/Cas9 system is that the cellular DNA repair machinery can introduce inaccuracies following a double-strand break (left panel). Nakajima et al report a new gene-editing method that avoids the formation of double-strand breaks. Cas9 nickase produces a combination of single nicks in the genome and the DNA carrying the repair template, resulting in precise and efficient gene editing (right panel).

Abstract

CRISPR/Cas9, which generates DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) at target loci, is a powerful tool for editing genomes when codelivered with a donor DNA template. However, DSBs, which are the most deleterious type of DNA damage, often result in unintended nucleotide insertions/deletions (indels) via mutagenic nonhomologous end joining. We developed a strategy for precise gene editing that does not generate DSBs. We show that a combination of single nicks in the target gene and donor plasmid (SNGD) using Cas9D10A nickase promotes efficient nucleotide substitution by gene editing. Nicking the target gene alone did not facilitate efficient gene editing. However, an additional nick in the donor plasmid backbone markedly improved the gene-editing efficiency. SNGD-mediated gene editing led to a markedly lower indel frequency than that by the DSB-mediated approach. We also show that SNGD promotes gene editing at endogenous loci in human cells. Mechanistically, SNGD-mediated gene editing requires long-sequence homology between the target gene and repair template, but does not require CtIP, RAD51, or RAD52. Thus, it is considered that noncanonical homology-directed repair regulates the SNGD-mediated gene editing. In summary, SNGD promotes precise and efficient gene editing and may be a promising strategy for the development of a novel gene therapy approach.

To learn more about this research, please view the full research report entitled " Precise and Efficient Nucleotide Substitution near Genomic Nick via Non-Canonical Homology-DirectedRepair " at this page of Genome Research .

Related links